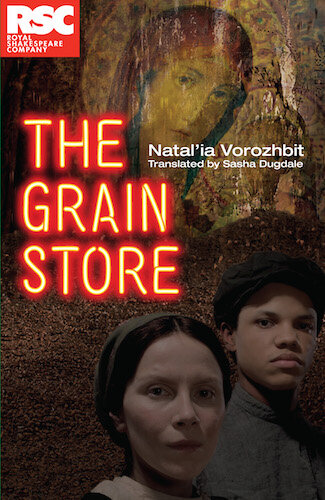

The Grain Store

By Natal’ya Vorozbhit

Translated by Sasha Dugdale

Genre: Drama, a fictional account based on actual events

Key Scenes: ACT I, Sc. Easter 1931: pp. 19-23, (5F, 7M); ACT II, Sc. 16 April 1933: pp. 54-56, (1F, 1M); ACT II, Sc. 23 April 1933: pp.66-70, (3F, 5M + Crowd)

Number of characters: 30+ (7+F, 10+M) Age recommendation: 12+ (death, starvation)

Country: Ukraine

Original language: Russian

Translation 1: English Translation by Sasha Dugdale

Translation 2: English Adaptation by Tonderai Munveyu, set in Zimbabwe

Description:

Based on the terror-famine that caused seven million deaths in Ukraine and neighbouring lands in the 1930s, Vorozhbit’s play illustrates the consequences of Stalin's first five-year-plan on a small Ukranian village.

A close knit rural community stands unwittingly in the path of Stalin’s drive to create a thriving socialist Soviet Union. The outcome is catastrophic. What begins for the people of the village as an amusingly alien concept, foretold by a group of agitprop performers, rapidly becomes a really and unstoppable force for change. Robbed first of their land, then their religion and independence, the whole country soon becomes engulfed by a tragedy that will scar a nation for generations.

The play centres primarily on the story of young lovers Arsei and Mokrina, who yearn to be married but cannot, at least to begin with, because he is a peasant and she is the daughter of a landowning ‘skilled’ farmer (kulak). In a twist of fate, the tables turn and Arsei becomes a communist enthusiast and climbs up the ranks of the Soviet regime, while Mokrina’s family is stripped of their possessions in the name of collectivism. The two are finally married, but at what cost?

The Grain Store was written in Russian and translated into English by Sasha Dugdale. It was commissioned by the RSC for its Revolutions season in 2009.

Videos

+ DETAILS

Play Title in Original Language: Зернохранилищe

Author: Natal’ya Vorozhbit

Publisher: Nick Hern Books, 2009

World Premiere (in the Engl. lang.): Royal Shakespeare Company at the Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, UK, in 2009

Translation 1: Sasha Dugdale

Translation 2/Adaptation: Tonderai Munyevu

Essay Writer: Molly Flynn

Education Pack Resource Writer: Alia Al Zougbi

Filmed Excerpt Director: Anthony Simpson-Pike

+ CHARACTERS

MOKRINA STARITSKAYA, 13 year-old daughter of Feodossi, a skilled landowning farmer (kulak). She is a fine singer and retains a strong spirit through the famine and suffering she endures.

ARSEI PECHORITSA, a young peasant who is recruited to Stalin’s regime and becomes a communist enthusiast. He is torn between his love for Mokrina and his loyalty for the state.

MORTKO, the regional government representative, strict and unyielding with the villagers. He rules with and iron fist and has no understanding of the delicate web of relationships in the village

FEODOSII, a financially comfortably landowning farmer who gradually loses his possessions to the Soviet regime through the process of collectivisation

OLIANA, Mokrina’s mother

ODARKA, Arsei’s mother

SAMSON and GOROBETS, two middle-aged friends who provide comic relief in parts of the play

KILINA, a beautiful young peasant girl whose love for Arsei is unrequited

RUDENKO, the local educator

ARTYUKH, the grave-digger

SAMOILENKO, the flesheater

OLD WOMAN, holds an empty bucket throughout the play, symbolizing the frugality of her existence, but even that eventually gets taken from her

See the full list of characters in the Education Pack here

+ ESSAY EXCERPT

The Grain Store: A New Kind of Theatre for Ukraine

by Molly Flynn

More than 3.9 million Ukrainians died of starvation in a man-made famine between 1932-33. Their deaths were a direct result of Josef Stalin’s collectivization policies which sought to centralize the distribution of grain and livestock throughout the Soviet Union. An essential strand of the policy was something called dekulakization (in Russian) or rozkurkulennia (in Ukrainian) which involved the imprisonment, deportation, and execution of millions of wealthy peasants whose land and property were subsequently seized by the state. Several regions in Russia and Central Asia also suffered immense loss of life during the process of forced collectivization but Ukrainian farmers and peasants bore the brunt of the suffering and starvation. In Ukraine and internationally this famine has come to be known as Holodomor, a designation that combines the Ukrainian word for hunger – holod – with the word for extermination – mor.

Read and download the full essay here

+ AUTHOR'S NOTE: Natal'ya Vorozhbyt

Translated by Anna Lukanina

Since I was a child, I heard about Holodomor from my grandparents. For some reason they were whispering, like if it was some sort of a different tragedy, not the same as World War II. When I grew up, I realized why. The Holodomor was a terrible crime of the Soviet regime, which we were forbidden to talk about. I was lucky that the Royal Shakespeare Theatre commissioned me to write this play, because I wouldn't dare to write it myself. The habit of keeping silent is stronger than the habit of speaking, and I inherited it from my intimidated ancestors.

While working on the play, I was always wondering, how big and strong my family would have been if my grandfather hadn't lost 10 sisters and brothers, and if my grandmother’s father wasn’t killed. I was thinking, what my country would be like now if nearly 10 millions of Ukrainians were not destroyed by the Soviet regime as a result of the artificial famine.

I also thought about human weakness and naiveté. About how people could so easily betray their relatives and neighbours and, putting up hardly any resistance, take the side of evil.

+ TRANSLATOR'S NOTE: Sasha Dugdale

Ukrainian playwright Natal’ia Vorozhbyt’s The Grain Store was first produced in English by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2009, as part of a Russian-language season, curated in consultation with the Royal Court’s International Director, the late Elyse Dodgson. It was paired in repertoire with a play called The Drunks by the Durnenkov Brothers, and a festival of play readings, featuring plays by Ivan Vyrypaev, Alexander Arkhipov, Yaroslava Pulinovich and others. The season overall represented the most comprehensive engagement with contemporary Russian-language theatre since the Royal Court’s work with new writing in the early 2000s, and it involved a huge number of theatre practitioners in the UK: not just directors and actors, but choreographers, DJs, puppeteers and even cooks.

The resources and the setting of the RSC meant that The Grain Store’s operatic scale and polyphony was given full rein in Sir Michael Boyd’s direction. The cast learned both Soviet hymns and Ukrainian folk songs, they danced in beautiful formation, they exploited the full range and scope of the writing, the frequent moments of wit and poetry which lighten this epic tale of famine and death. The show opened with long tables, laden with real food. Audience members were invited to join the cast for borshch and dumplings, so accentuating the sense of almost awestruck surprise and horror felt by the community as the food disappeared.

Natal’ia’s writing is always exuberant and full of wonders, and as the translator of The Grain Store, I loved working with this rich material. I felt that the liveliness and even playfulness of her text; the puppet scenes, the slapstick and the agitprop songs – in short, the life pulsing through the play – allowed the reader and audience to also experience the depths of tragedy and horror when all this life was curtailed and destroyed. During the weeks of rehearsal Natal’ia was asked to draft several new scenes and these were often irrepressibly funny or slapstick, performing a counterpoint to the sense of doom with which a cast and audience might approach a tale of genocide. Her fellow countryman the writer Nikolai Gogol, was described by Pushkin as making people ‘laugh through tears of sadness and tenderness’ and this might equally well describe Vorozhbyt’s approach to historical epic.

The Ukrainian famine, the Holodomor, is one of the most tragic genocides of the twentieth century in Europe and yet most people in Western Europe don’t even know it happened. The Grainstore is a magnificent, life-affirming memorial to the millions whose lives were taken in 1930s Soviet Ukraine.

+ ADAPTOR'S NOTE: Tonderai Munyevu

It’s been so fascinating reading Natalia’s play as it struck me to be at once very Eastern European and very African. Of course when we look at the politics of each country we see that there are a few similarities which derive from an attempt at socialism that has major percussions for those living under such political ideology. The idea of the “peasants” really resonated with me. In any political system this group is always the one that has to deal with the fall out of high ideas that subject to human greed at the top, become devastating for those whose lives are subject to the produce of the land.

The scene where the local community are made to dance and enjoy themselves while starving to appease the visiting dignitaries will stay with me forever. This was my starting point translating another scene which was actually quite comic. I thought the idea of the Grain Store itself was fantastic. Grain (Chibage—maize meal) in Zimbabwe is in everything, the absence of it means starvation. It seemed to link in very easily with the idea of relocating the play to Zimbabwe. it brought into sharp focus the hunger that was bestowed on the Ndebele people while the world was referring to Zimbabwe as the “breadbasket of Africa.” Anthony Simpson Pike and I also like that humour is a huge part of the Zimbabwean condition of dealing with strife.

We relocated the action to a little reported suppression of the Ndebele tribe by the predominantly Shona government. I added a touch of magical realism which to me is always a hallmark to Shona ritual and this for me places the play in the continuum of the human experience which brings us back to Natalia’s Grain store: human oppression by other humans is an everlasting occurrence, and so is artistic expression in the service of alleviating that suffering both in witnessing and in participation.

Production Images

Original (Russian) & Translation 1 (English)

Translation 2 (English)

Cast and Creatives

Molly Flynn

Academic Essay Writer